Directed by Guillermo Del Toro — Screenplay by Guillermo Del Toro.

There are literally hundreds of films either directly based on or partially inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, so the story of Victor Frankenstein (and his creature, or monster, that is often wrongly referred to as just ‘Frankenstein’) is one that audiences of most ages know quite well either through having seen films based on the story or through references in pop culture that, with stories as familiar as this one, tend to fasten in your audiovisual language through a process of cultural osmosis. One auteur, however, hopes that his passion project can add something new to the storied legacy of the character, and now Netflix has given that opportunity to that auteur. I am, of course, referring to Guillermo Del Toro, the Oscar-winning filmmaker with a known love for classic monsters, creature effects, and both horror, fairy tale, and gothic storytelling. It should be a match made in heaven, and, frankly, I do think the wait for Del Toro’s take on Frankenstein, his 13th feature film as a director, was worth the wait.

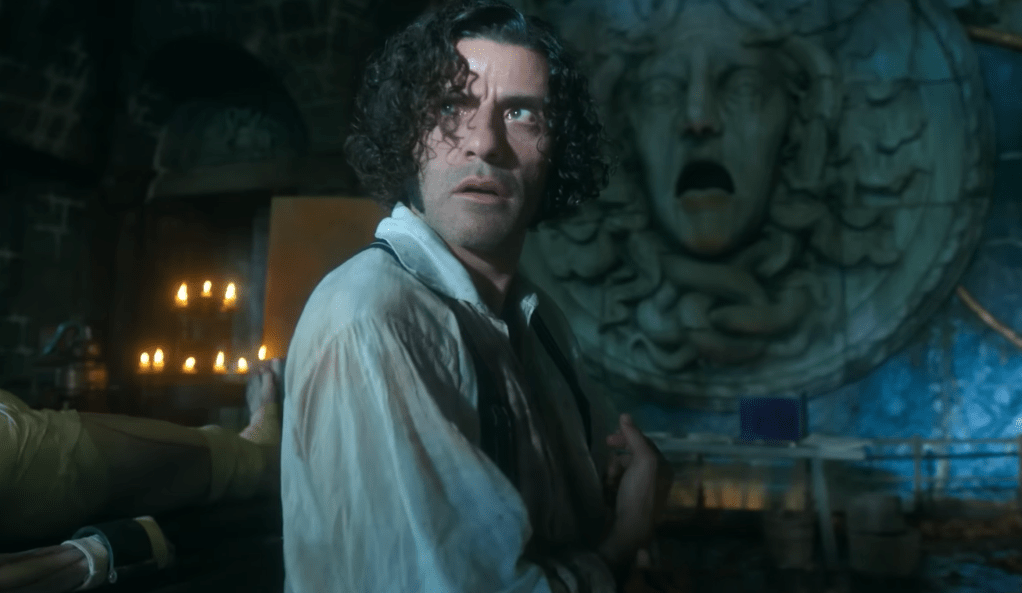

Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein opens in 1857, which is notably a handful of years after author Mary Shelley’s death in real life (and several decades after her book was set). At this time, we encounter a Royal Danish Navy expedition ship, called the Horisont, headed for the North Pole but currently trapped in ice. After seeing fire in the distance, Captain Anderson (played by Lars Mikkelsen) has his crew pick up an injured man and bring him aboard; however, something loud and big is out there on the ice. As the Danish crew try to keep this creature from getting hold of the injured man, who, it turns out, is Victor Frankenstein (played by Oscar Isaac), Victor tells his life story to the Danish captain, who soon learns that it was Frankenstein who created the monstrous creature (played by Jacob Elordi) that now threatens the life of the Danish crew and the expedition’s mission. The story then unfolds as the ship captain is told Frankenstein’s story, and, eventually, the creature’s own version of the events that followed.

Whether in my reviews of El Laberinto del Fauno or Pinocchio, or elsewhere, I’ve often written about what I lovingly call the Guillermo del Toro formula. His films are almost always about finding or showing kinship with, or the comfort of, the magical or spiritual beings (ghosts, monsters, etc.), as he seeks to highlight the real monstrosity of real-life traditions, mad men, or societal norms. Indeed, he often sets his tales against a backdrop of war or significant societal change, like the Spanish Civil War in The Devil’s Backbone, the rise of fascism in Pinocchio, or the Cold War in The Shape of Water. That formula is, or those interests are, also apparent in his Frankenstein, which, as I understood it, partially uses the Crimean War of the Mid-19th century (and has the central creature of the film be a creation made up of the victims of war put together by those privileged enough to pay the war no mind), but, perhaps more significantly, focuses on the traditional values of the era being confronted with scientific enlightenment and boundary-testing ideas just a few years before Darwin advanced the idea of evolution, which, of course, changed our understanding of history and biology forever. The film pays particular attention to traditional society lambasting boundary-testing ideas, rejecting those that look different, and scientific advancement having such a fervent pace that patience is difficult to accept.

Del Toro’s film eventually gives us a gradually more and more intelligent, kind (despite his monstrous strength), and beautiful (despite him being a patchwork creation) Frankenstein’s monster, and Elordi plays him with such humanity and a deep emotional response, whether that be rage or sensitivity. His performance, despite him perhaps not being the most obvious casting choice, is one of the film’s strengths. It isn’t just Elordi who is particularly good. Oscar Isaac does a good job of encapsulating Victor Frankenstein’s larger-than-life ambition, expectation, and eventual arrogance. Mia Goth has a sensational screen presence in a perhaps slightly underwritten role. And then there are just numerous note-perfect character actors like David Bradley, Lars Mikkelsen, Christoph Waltz, and Charles Dance, all of whom are so good that I can’t see anyone else play their specific versions of their characters.

The film has a lot in common, in particular, with Del Toro’s Crimson Peak and Pinocchio. For one, it has that Victorian Age gothic design to it that is just brought to the screen so well. I love how Del Toro and costume designer Kate Hawley tell the story through the use of black, red, white, and green, and, in addition to the narrative decisions that have gone into the colors of the film, it also just looks spectacular. The same goes for the production design. From the almost retrofuturist gothic coffins to the design of Frankenstein’s tower, the film is rich in detail, and the locations, along with the costumes, have lives of their own. The creature designs are also just so well-realized. The central creature has an appropriately Prometheus-esque look in some scenes, the inspired look of the almost horror-like torso that Victor shows off to high society gives you a pleasing move-forward-in-tour-seat type of scene, and then you have the recurring nightmarish fiery crimson angel that is still stuck in my head several days after I first saw the film. I think the film looks sensationally good despite certain digital limitations.

As for the Pinocchio connection, I think the way Guillermo Del Toro uses the story to highlight creation and fatherhood is really inventive and moving. The film sees Victor despise but still become his own father gradually, and the film does a good job of making this explicit without making it feel like you’re being hit over the head with it. I can’t stop thinking about the film’s ideas about the confused burden of being created but despised or deemed unsatisfactory, as well as the difficult but necessary act of forgiving someone to free yourself of that burden and finally live your life. I found these ideas, and the ending of the film, to be both poignant and beautiful. I think it speaks to a lot of complex parent-child relationships out there.

I already mentioned how I feel that Goth’s character could’ve benefited from more of a focus. But while I absolutely loved the experience of watching this film, I do have one or two additional issues that merit mentioning. For one, I do think the central idea that the real monster in the narrative isn’t so much the actual ‘monster’ but rather its creator is such a well-known idea that whenever the film speaks to it directly, it feels unnecessary and a little bit on the nose. Finally, I do agree with other critics who have opined that the computer-generated forest animals kind of take you out of the experience of the narrative in the brief moments that they’re on-screen. Having said that, those creations in that small handful of scenes are never so off-putting that they take away from the film’s effect on me, when it’s all said and done.

There are so many films about Frankenstein, as well as some undeniable classics, so I won’t go out of my way to say that this instantly becomes the quintessential version of the narrative. That said, I loved Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein for its poignant themes, its lavish costumes and sets, and its many note-perfect performances. I loved being in the world Del Toro created during its runtime, and I’m excited about the opportunity to return to it on rewatch. Guillermo Del Toro set out to do something quite difficult by making another adaptation of a classic story. Del Toro has lived his dream by making his most desired passion project. He has put energy into his creature, awoken it, and he now hopes that it has been worth the wait. Rest assured, Guillermo. Your creation isn’t monstrous. It is, through all its strengths, both operatic, epic, beautiful, and, most importantly, human.

9 out of 10

– Review written by Jeffrey Rex Bertelsen.

One thought on “Frankenstein (2025) | REVIEW”