Directed by Danny Boyle (Yesterday) — Screenplay by Alex Garland (Annihilation).

Nowadays, we’re inundated with zombie, or zombie-adjacent, entertainment, which, once upon a time, was popularized by George A. Romero. But before The Last of Us and before The Walking Dead, there was an early 2000s zombie movie revival — e.g., the Resident Evil film adaptation, Shaun of the Dead, and 28 Days Later — the effects, influence, and iconography of which are still being felt to this day. Two of the primary voices in this revival — though I doubt they thought of themselves as such — were Danny Boyle and Alex Garland, the director and writer, respectively, of 28 Days Later. Here was a film, which was filmed in the UK at the time of the 9/11 attacks in the US, about civilization breaking down, about how quickly we can be turned into people blinded by rage, and about how important it is to hold on to our humanity. Now, 23 years later, following both Brexit and the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown, Garland and Boyle have re-teamed to continue the story of the rage-virus that shook their world and humanity’s varied response to it with 28 Years Later. It’s one of the most anticipated genre films of the year, but does it live up to all the buildup? Well, I really like this film, but, due to certain elements that are sure-to-be divisive, I think it’s only fair to say that the answer must be a tentative ‘yes and no.’ Let’s dive in.

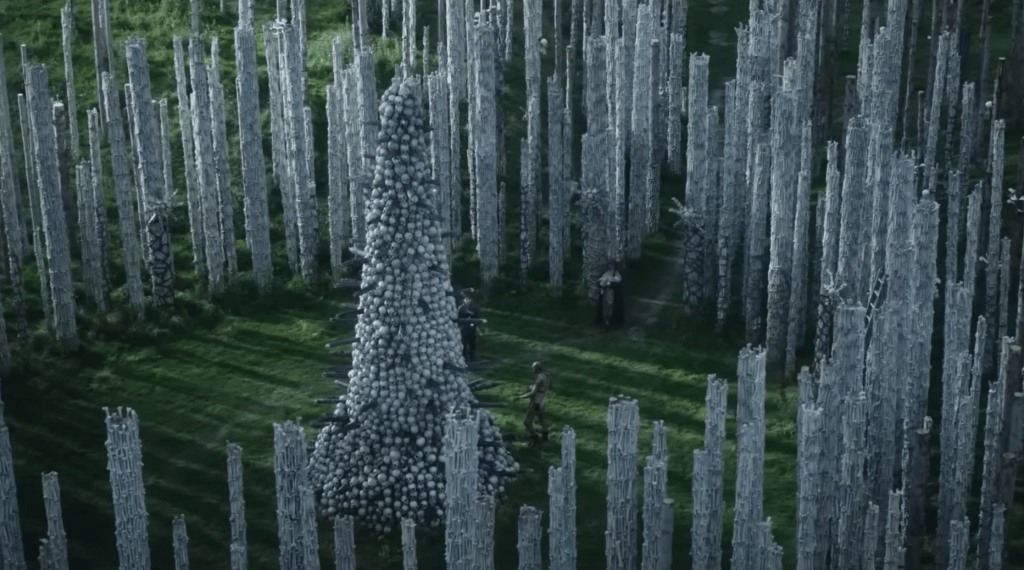

Danny Boyle’s long-awaited 28 Years Later, naturally, takes place 28 years after the outbreak of the so-called ‘rage virus,’ as depicted in 28 Days Later, and the film follows a 12-year-old boy named Spike (played by Alfie Williams). Spike lives with his hunter-father, Jamie (played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson), and his bedridden mother, Isla (played by Jodie Comer), on the tidal island known as Lindisfarne (or Holy Island) in North East England in a relatively heavily fortified village community, whose societal lifestyle is fairly old-fashioned or antiquated. On their island, young children are trained to use a bow and arrow so that they can become hunter-gatherers for the community. Though the children are usually fourteen or fifteen before they get to go on guided visits to the dangerous mainland where many different types of infected roam, Jamie has insisted that Spike is old enough and ready to do it already at age twelve, despite Isla’s protests. On Jamie and Spike’s perilous journey into the mainland, Spike has his first encounter with the infected and sees a mysterious fire in the distance. When Spike starts asking questions about who lit the fire, he formulates an idea about how he may be able to save his mother from the illness that has left her confused and bedridden.

In addition to popularizing the idea of fast zombies (though their film’s infected aren’t technically decomposing undead), Danny Boyle, Alex Garland, and cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, with 28 Days Later, also opted for a very distinct look by using Canon XL1 digital video cameras to shoot in standard definition. The result was a gritty look that added to the atmosphere and realism of it all, and the action was shot and edited in a way that felt frenetic. It’s one of the only major motion pictures of that era that looks like that, and, for this legacy sequel, they’ve done a similar thing. Instead of solely shooting on fancy professional cameras, like 28 Weeks Later was (which Boyle, Garland, and Mantle did not work on), portions of the film are, once again, shot on cameras that literally anyone could shoot a movie on. In the case of 28 Years Later, they went for an iPhone 15 Max. The result is a markedly different and not quite as gritty look, but the sense of realism is sometimes perfectly executed. As for the action, the crew crafted these giant rigs of many iPhones to instantly capture the action, and it is presented in a stylistically stuttering, bullet time or instant replay-esque fashion that is quite unique. In addition to this, there are insert shots of Laurence Olivier’s Henry V, and the film uses this infrared or red-ish night vision for dream sequences and shots of the infected going berserk. In total, it makes for a fascinating, multi-faceted visual presentation that also, notably, manages to be both grisly and gorgeous, as there are also scenes with either a kaleidoscopic backdrop or scenes where the colors of nature stand out.

It is a film that is filled to the brim with ideas. It is, at once, a coming-of-age film about a child coming to terms with death, deceit, and the dangers of the world outside of his front door, but also a film deeply concerned with themes of isolationism, cultural regression, nature versus nurture, and the film as a whole, quite clearly, serves as an allegory for Brexit (e.g., the UK is isolated, the central community in the film is concerned with antiquated, gendered job roles, they fear the mainland, and there’s clearly a touch of nationalism to them given the framed picture of a young Queen Elizabeth II on a wall). There is a lot of religious symbolism (some of which work better than others), and the film is also clearly concerned with children growing up too fast or not growing up at all. There are characters here that are clearly unhealthily obsessed with 90s entertainment, as they grew up with Teletubbies and, disturbingly, dress like Jimmy Saville. The film really is jam-packed with themes, ideas, and cultural references that make this a rich experience, though, at the same time, perhaps, to some, the throwing stuff at the wall to see what sticks technique (as I presume the film’s naysayers would call it) can perhaps also work against the film.

Structurally, each act is quite distinct. Without going into spoilers, the first act delivers on the kind of intense zombie-esque rage virus action that many probably sought out the film to see. The second act, however, is where the film changes direction slightly and becomes a coming-of-age film. As the film transitions from act two to act three, the film starts making some curious choices with one character bringing in some levity (that I think may rub some people the wrong way) and the film, later, making some decisions about the lore of the rage virus and the infected that may bend traditional zombie movie rules. However, it is in the third act that the film rises to another level. As Ralph Fiennes joins the action, the film’s beating heart becomes clear for all to see, its focus on humanity rather than the undead is emphasised, and, notably, the film tugs at your heartstrings with a scene that I thought was incredibly moving and far more touching than what I expected from this type of film. In general, I found the film to be uniformly well-acted, but it is Fiennes’ humanist doctor and newcomer Alfie Williams who make the strongest impressions, with the latter of the two managing to carry the film on his back as if he were a seasoned pro. I do, however, think the film ends slightly awkwardly with a scene that would’ve worked better as a post-credits scene. It is a scene that not only gives you tonal whiplash but also makes some character decisions that, now that I think about it, feel more at home in the world of Mad Max than in 28 Days Later.

I’m sure that curious final scene will be incredibly divisive, or even a dealbreaker, to some. But, on the whole, I felt invigorated by how inventive and idea-heavy the film was, I was wowed by the affecting third act, and, despite some tonal issues, I was impressed by the gutsy big swings that Danny Boyle and Alex Garland made here, which is refreshingly different from the many overly safe legacy sequels nowadays. Admittedly, I don’t think 28 Years Later is quite as good as the original film, but it has a big beating heart, a head full of ideas, and audiovisual artistry that, in total, makes for a really good time at the movies with plenty to chew on.

8.7 out of 10

– Review written by Jeffrey Rex Bertelsen.

2 thoughts on “28 Years Later (2025) | REVIEW”