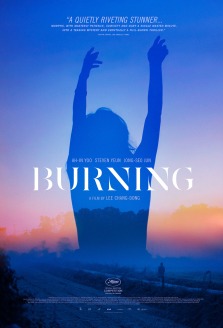

The following is a review of Burning (‘버닝‘) — Directed by Lee Chang-dong.

There are a couple of news reports during the first hour of Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. During the reading of these reports, the frustrated Lee Jong-su (played by Yoo Ah-in) is walking through his family home, a farm house so close to the North Korean border that he’s able to hear North Korean propaganda out in the open. As he is walking through the house, we hear how his generation is struggling to find work in South Korea, and we also see President Donald Trump on a television screen.

These background noises that color our reading of the main character’s life, define much of the struggle at the heart of the film which places a young man bound to his family home against the free, wealthy, but numb man played by Steven Yeun. This is a film about the here and now. South Korean class struggle, frustration, and loneliness are just some of the many fascinating layers to what is a deeply mysterious but not necessarily subtle drama that transforms more than once over the course of the intimidating 148-minute runtime.

Based on Haruki Murakami’s short story “Barn Burning,” — which is a short read that I would recommend that viewers seek out after they’ve seen the film — Lee Chang-dong’s Burning is a psychological drama which becomes a different film as it goes along, and once it comes to its conclusion, it does so with a likely unforgettable final scene. The film follows the aforementioned Lee Jong-su, a living embodiment of an expectation to stick by a much older more rural lifestyle in South Korea, as he works these meaningless jobs while his father is in trouble with the law.

One day, while working one of the meaningless jobs, he locks eyes with a young woman named Shin Hae-mi (played by newcomer Jeon Jong-seo), who insists that they knew each other when they were younger. She informs Jong-su that she has gotten some plastic surgery done on her face, which, it is later revealed, might have been a direct result of a mean-spirited comment he made about her in school. She then rigs a game so that he wins a nice watch, they stand side-by-side and smoke in an alley, and then they decide to go to dinner.

One thing leads to another, and they end up in bed together in her tiny apartment. But their romance is fleeting. Soon, Hae-mi asks Jong-su to look after her cat — which is nowhere to be seen — and her apartment while she travels to Africa, and he agrees without question — he is falling for Hae-mi. Days go by and Jong-su becomes more and more lonely, when she finally — all of a sudden — calls him to say that she is coming home.

When he meets her in the airport, she is with another man — Ben (played by Steven Yeun), a handsome and very wealthy man a few years their senior, who, perhaps, is a living embodiment of a new, Westernized side of South Korea. Jong-Su, who is also an aspiring writer, likens him to Jay Gatsby in a scene that reminded me very much of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic line: “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.” But being called Gatsby isn’t really a compliment in this case.

But is that all he is? Odd condescending but somehow friendly comments from Ben confuse Jong-su, who, when Hae-mi stops answering his calls, then starts to investigate her puzzling new man and his peculiar ‘hobby’. To say more, would be to ruin the rewarding experience of watching one of the year’s best films, which is filled to the brim with ambiguous details and themes that are well-balanced and spread out over the lengthy but not arduous runtime.

Burning is one part class-conscious love story, one part love triangle, and, finally, one part psychological thriller, and watching Lee Chang-dong’s film move from one, to the next, to the last is riveting. It is rich in visuals, references, mystery, and clues, and yet Chang-dong’s film seems conscious of its limiting point-of-view as the film is seen from the perspective of a frustrated but oblivious young man on the brink of losing the one good thing in his life.

His treatment of Hae-mi is, at best, questionable. He is a writer without passion to write or experiences that he wants to write about. His readings of the other characters are fascinating and will likely be the source that most post-viewing discussions will start to analyze to gain an understanding of the film, the final scene, and the entire film’s presentation of metaphors, truths, and half-truths.

I see a firey frustration in Jong-su’s eyes. I see a writer struggling with what he wants to write. I see a writer learning to live life and feel the bass in his chest of which only those that are more privileged than himself have an understanding. I see a class struggle, loneliness, frustration, and jealousy, but I also see a man oblivious to the power of ill-measured comments. In another character, I see both sociopathy and a sad cultural and emotional numbness which is birthed by a different kind of loneliness entirely. I see an inconclusive and deeply ambiguous ending that can lead to many, wildly different readings that are all credible. I see many of these different readings at once, and I feel satisfied with a film that is up for interpretation.

I am spellbound by the free-spirited but gullible and sad Hae-mi — played wonderfully by Jeon Jong-seo — dancing in the evening trying to feel the life that she wants to live. I am at once both frustrated with and frustrated for Yoo Ah-in’s Jong-su. Finally, I am charmed but frightened by Steven Yeun’s Ben. Yeun, who many western audiences know best from his time on AMC’s hit The Walking Dead, graduates into stardom with a charismatic and enthralling performance that had me hang onto every word he spoke.

Since I saw it in a mostly empty theater yesterday — sitting nearby someone who was half-asleep for the second hour of the film — I have been unable to get the mystery and the narrative out of my mind. I constantly think back to Yeun, especially, but, really, all of the three lead characters and the way they acted, changed, and vanished in one way or another. Lee Chang-dong’s Burning is a meditation on class struggle and youthful frustration and loneliness in the form of a mystery film. I think that even those put-off by the runtime will find enough in the final act to chew-on to have a worthwhile experience, but those who dig-in to what Lee Chang-dong’s film gives you will be rewarded with a thoughtful, layered but unsubtle, and undeniable slow-burn South Korean masterpiece.

10 out of 10

– Jeffrey Rex Bertelsen.

4 thoughts on “REVIEW: Burning (2018)”